Who Put Bella in the Wych Elm?

A chance discovery of a body in 1943 led to a bizarre local legend of witchcraft, espionage and murder. But who put the body in the tree?

In the Stephen King novella The Body (adapted for the screen as Stand By Me) four preadolescent boys embark on an adventure to seek out the body of a fifth boy who had recently disappeared. Acting on stolen intelligence that concerned the location of the boy’s body, the four lads set out to find it.

Despite the finding of a human body being their specific object, the actual discovery is a shocking moment and the boys are naturally upset to see death in its undeniable physicality.

Upsetting though it was, it would perhaps have been worse had they not been expecting to find a body. Pity then, a cohort of four friends in wartime England.

In April 1943, our four preadolescent boys embarked on an adventure of their own. Their object: to seek out bird nests. Trespassing on Lord Cobham's estate near Wychbury Hill in the English Midlands, they found a large wych elm, which they believed would be an ideal location.

As one boy, Bob Farmer, climbed the tree, he happened to glance into the hollow trunk. A pale skull glanced back. Believing it to be that of an animal, he reached in and grabbed it. It had human hair and teeth. The boys had found human remains.

Having made their discovery, the four boys did what any group of intrepid lads would do: they put the thing back where they found it and vowed to tell no one that they had been there at all.1 However, wracked with guilt, one youth decided to confess all to his parents.

When the police searched the tree they found an almost complete skeleton along with a shoe, a gold wedding ring, and some fragments of clothing. A hand was found some distance from the rest of the body.

An inquest heard that the body was that of a woman of around 35 years of age. She had mousy brown hair and stood around five feet tall. She had been wearing a dark blue striped cardigan and a long skirt. The bones gave no evidence of violence but a section of peach-coloured taffeta from underneath her skirt had been stuffed deep into her mouth. That suffocating cloth was the pathologist’s best guess as to the cause of death. The evidence of decay suggested that her remains had lain there for about eighteen months. The verdict: ‘murder by some person or persons unknown’.

That unknown person or persons seems likely to have planned their crime. It was the opinion of the pathologist that the body was placed in the tree post-mortem. He could not imagine anyone getting into the small aperture on the tree voluntarily. Nor could a stiffened body be easily placed inside. The body must have been placed in its arboreal grave very shortly after death.

Reconstructing events from such paltry evidence is difficult. It is not clear, for example, whether the killing took place near to the tree, or whether it happened elsewhere with the body transported by the killer or killers. Either way, the woman's final journey would have been by human foot: the site was not directly accessible by road. A five-bar gate around 30 metres away was the nearest point at which a vehicle could obtain. The trip was also likely a nocturnal one. The general area of Hagley Wood was popular with visitors. Daylight would have risked discovery.

This was clearly an impractical dumping ground for a body. It would have taken effort to place the body there. The corpse may have been concealed for eighteen months but only for eighteen months. There were surely more suitable locations for a killer to hide their handiwork.

Unless, of course, the location itself was significant. The severed hand and placement of the body in a wych elm was suggestive of ritual or some spirit of witchcraft.

Back in the realm of the real, the police made enquiries. The woman's jaw had an unusual shape which would have given her a distinctive appearance in life. In theory, this should have made her identity easy to determine. However, despite a review of medical and dental records and an audit of missing persons, no identity was established. Every trail would prove cold.

The graffiti started to appear the following year. Daubed on a wall on Upper Dean Street in nearby Birmingham were the words ‘Who put Bella down the Wych Elm?’ and ‘Hagley Wood’. The tree and the location matched the find. The name Bella was new. Who was Bella?

‘Bella’, it would appear, was a fiction. In the early 1950s police traced the graffito. He was, according to the lead officer, Detective Superintendent Tom Williams, ‘a crank who knew nothing and who had nothing to do with the case’.2 Whoever she was, the woman was not ‘Bella’. But the name stuck.

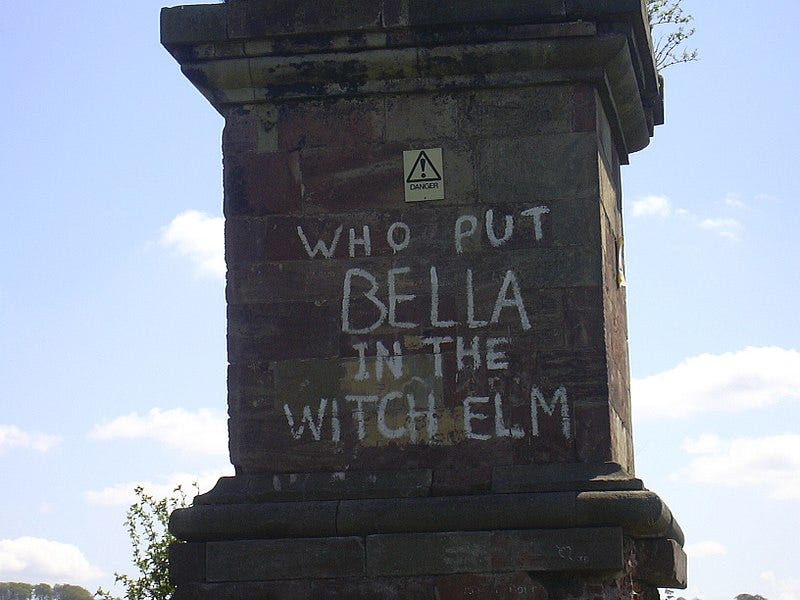

As did the graffiti. References to Bella and the wych elm kept appearing in scruffy spraypaint scrawls across the West Midlands until 1999. The Hagley Obelisk was a particular target. There were some variations on the text -the name 'Bella' was occasionally expanded to 'Luebella' and 'wych' was sometimes rendered as 'witch' but there were no plausibly real connections to the case.

What the graffiti did achieve was a constant low-level interest in the crime. The case was reopened in 1949 after a man came forward with new information. This man, a serving soldier, claimed that he had seen ‘a party of gipsies in Hagley Wood very near where the body was found’. This itself wasn’t unusual: the site had been used by the Traveller community in the past and, it has to be said, it wasn’t especially remarkable for these people to be blamed for any crime without an obvious perpetrator, but the police were satisfied that the man had information that wasn’t otherwise available to the public.3

The same cannot be said for the other individuals who reported ‘clues’. In 1953 the lead detective despaired that while people were happy to report that they had information on the victim, ‘none of them seemed to have a clear idea of [her] appearance’.

The most high-profile of these speculative reports came from a woman by the name of 'Anna', who claimed to have information about the dead woman's origins. This pseudonymous theorist from Claverley in Shropshire wrote to DS Williams in 1953. Tellingly, she also wrote to the newspapers at the same time.4

Her letters bore the claim that the case involved no ‘witch, black magic or moonlight rite’. The victim had in fact been a Dutchwoman who had arrived in the UK illegally in 1941. The dead woman had been known to the letter writer, as had her killer, who, the letter went on to claim, had died ‘insane’ in 1942, the year before the body was discovered. Both victim and killer were ‘now beyond the jurisdiction of earthly courts’. No surname was given and no one in the posted location of Claverley in Shropshire could shed any light on the letter’s author.5 The police were eventually able to trace ‘Anna’, but were satisfied that the information had no bearing on the case and that their correspondent could be consigned to the crank file.6

Here, she could join the prolific crime writer and fabulist Donald McCormick, who expanded the thin evidence into a book 'Murder by Witchcraft', which conflated the case with another local murder that had been draped by rumour in the clothing of the occult. In the course of pursuing these connections, McCormick followed the already debunked Dutch connection. In McCormick's telling, the victim had been a Dutch spy who had been the lover of a Nazi by the name of Lehrer. Our woman, codename: 'Clara', had learned Birmingham-accented English before being dropped by plane in the Midlands under cover of an air raid. McCormick's lead was a fugitive Nazi, 'Franz Rathgeb', who was living under an assumed name in Paraguay and who recalled seeing 'Clara' at a party at which they had discussed astrology.7

By this point, the appendix aspects of the case all ran into one another. The witchcraft. The espionage. The sheer implausibility. It should have been clear to anyone, not least of all the detectives, that the case itself would remain unsolved. Barring some improbable intervention of new evidence, it will remain so forever. In that absence, all we have left is the crank. And, of course, the body. Someone put her in the wych elm. But who?

They feared getting into trouble with the law. Birdnesting wasn’t illegal in the UK in 1943, but trespassing was.

Birmingham Daily Gazette Saturday 28 November 1953.

Birmingham Daily Gazette Tuesday 4 October 1949.

Birmingham Daily Gazette Saturday 28 November 1953.

Daily Express, Thursday 26 November 1953.

Daily Herald Monday 7 December 1953.

Donald McCormick, Murder By Witchcraft, John Long, 1968.