Of Years All Winter

The explosion of Tambora in 1815 blasted dust and debris into the sky. It also birthed the modern culture of horror.

Of the eight ascending iterations on the Volcanic Explosiveness Index, the 1815 eruption on Tambora ranks seven. That achievement is unlocked by any blast in excess of 100 cubic kilometres of ejecta and with a cloud column height that extends into the stratosphere.

For the convenience of the unscientific, each level of the scale has a Beaufort-style description, which would threaten to make every category a little too sweet until you look at them. Level seven is three whole orders of magnitude above 'cataclysmic'.

Seven's descriptor of 'mega-colossal' still feels strangely inadequate. Tambora, located in Sumbawa in Indonesia, began its eruption on the 10th April 1815. During the event, an estimated 25-30 teragrams of sulphur alone were pumped into the atmosphere.

Teragram, now there's a word you don't hear every day. For tangible illustration: the Great Pyramid at Giza probably weighs just one.

You can't throw 25-30 Wonders of the Ancient World of debris and dust into the atmosphere without noticing any impact. Tambora's cloud hung heavy in the air, darkening the sky and dropping average temperatures by between two and five degrees. The cold, bleak months that followed were then called 'the year without a summer'. We would call it a nuclear winter.

The climatic effects were felt for years. Snow fell in southern Italy, which would have been enough of a rarity even if the flakes hadn't been yellow and red. Crops failed, further strangling an economy that had already been choked by the Napoleonic Wars and their after-effects.

And in 1816, it rained 'incessantly', creating misery for holidaymakers in Europe. For one particular group, taking a break at the Villa Diodati in Geneva, there was no choice but to take refuge indoors and make their own entertainment. The group, which included Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, his wife Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and John Polidori, whiled away the hours by telling stories to one another. Inured, to a certain extent, by their wealth they were surrounded by a peasantry that had taken to surviving on 'sorrel, Iceland moss and cats'. The combination of near-revolutionary starvation and the sunless sky set a particular kind of mood and prompted stories that could hardly be described as jolly.

The friends sat up and took it in turns to read aloud from Tales of the Dead a horror anthology that had been translated from a French edition entitled Fantasmagoria. At Byron's suggestion, they then decided to come up with their horror stories of their own.

Mary Shelley, as is well known, came up with an account of the misadventures of an intense medical student who stitches together a collection of cadaverous limbs before giving the resultant 'Creature' life.

For his part, Polidori composed a sinister tale of an undead aristocrat, Lord Ruthven, who was based apparently on Byron himself, being 'more remarkable for his singularities than his rank', who preys on high society and distributes charity like a curse.

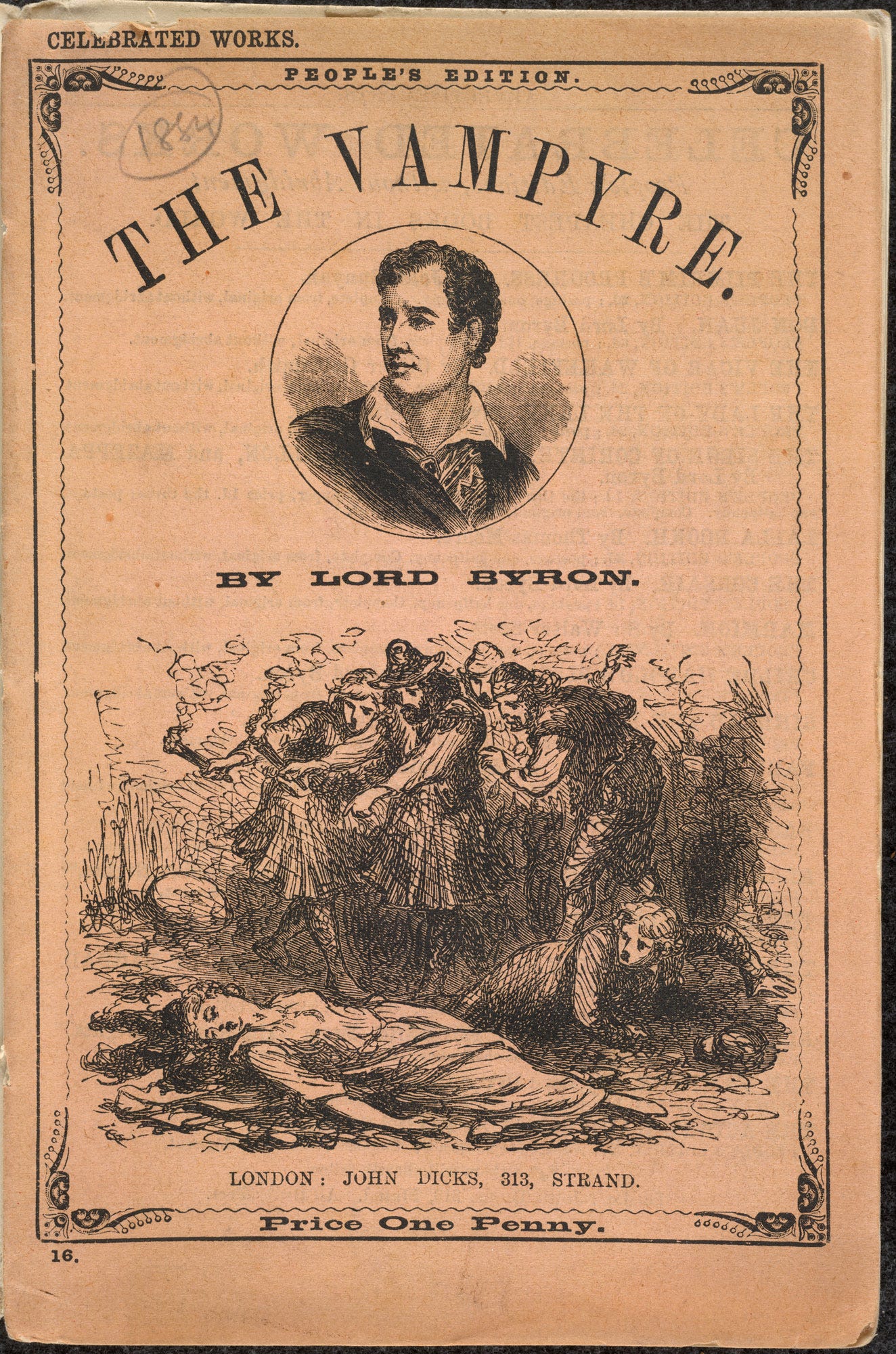

The story, which Polidori titled The Vampyre, had an odd publication history. First published in the New Monthly Magazine, where it was incorrectly attributed to Byron himself, partly because the protagonist shared a name with a Byron-like character in another novel, but more likely because Byron's notoriety was a valuable marketing angle.

Despite both Byron and Polidori denying Byron's authorship, the confusion persisted. In the following issue, dated May 1, 1819, Polidori wrote to the magazine's editor explaining 'that though the groundwork is certainly Lord Byron's, its development is mine'.

Nevertheless, the Byronic connection, along with the public's interest in gothic horror, contributed to the story's immediate success and meant that the template of the suave, aristocratic bloodsucker was imprinted on the public mind. Later works by Bram Stoker, F.W. Murnau and the films by Universal and Hammer, fixed it in the culture. Today, to think of a vampire is to think of Byron.

Why were they compelled to spook one another? It's a tempting speculation that the darkness of the sky had something to do with it. Shelley's story, which begins and ends in the icebound northern polar regions, is frequently cold and bleak in its setting, and refers to rain pouring 'from a black and comfortless sky'. Polidori saw fit to quote Byron's Childe Harold's Pilgrimage in the preamble to his story, with its descriptions of 'phosphoric seas' and 'years all winter'.

Although the horror genre has widened, those two archetypes remain prominent and those 'years all winter' the essential horror setting. Our cultural landscape remains in the shadow of that sulphuric fall two hundred years ago.